The Space Between Declarations: On Haochen Ren’s Art

There is something elusive at the heart of Haochen Ren’s work—an idea that resists being pinned down, like a breeze rearranging the dust in a quiet room. Born in Beijing in 1995 and now based in London, Ren moves within the field of conceptual art, mapping the thresholds between seeing and saying, between presence and withdrawal. His materials—acrylic cubes, exhibition labels, borrowed spaces—are disarmingly simple, yet they hold within them the same conceptual weight as a question left lingering too long in the air. To enter a project by Haochen Ren is not to be shown something. It is to be asked: What are you seeing, really? And what part are you playing by simply being here?

In a time where contemporary art often shouts to be heard, Ren whispers. He whispers not to obscure meaning, but to draw the viewer close. His is a quiet art—not in volume, but in intent. His interventions live on the margins of the visible, often taking the shape of what most would overlook: a gallery label without a work, an object without a label, an exhibition space that declares itself as lent rather than owned. These gestures are not acts of rebellion. They are invitations to reconsider what we believe we know about art, and how we come to know it.

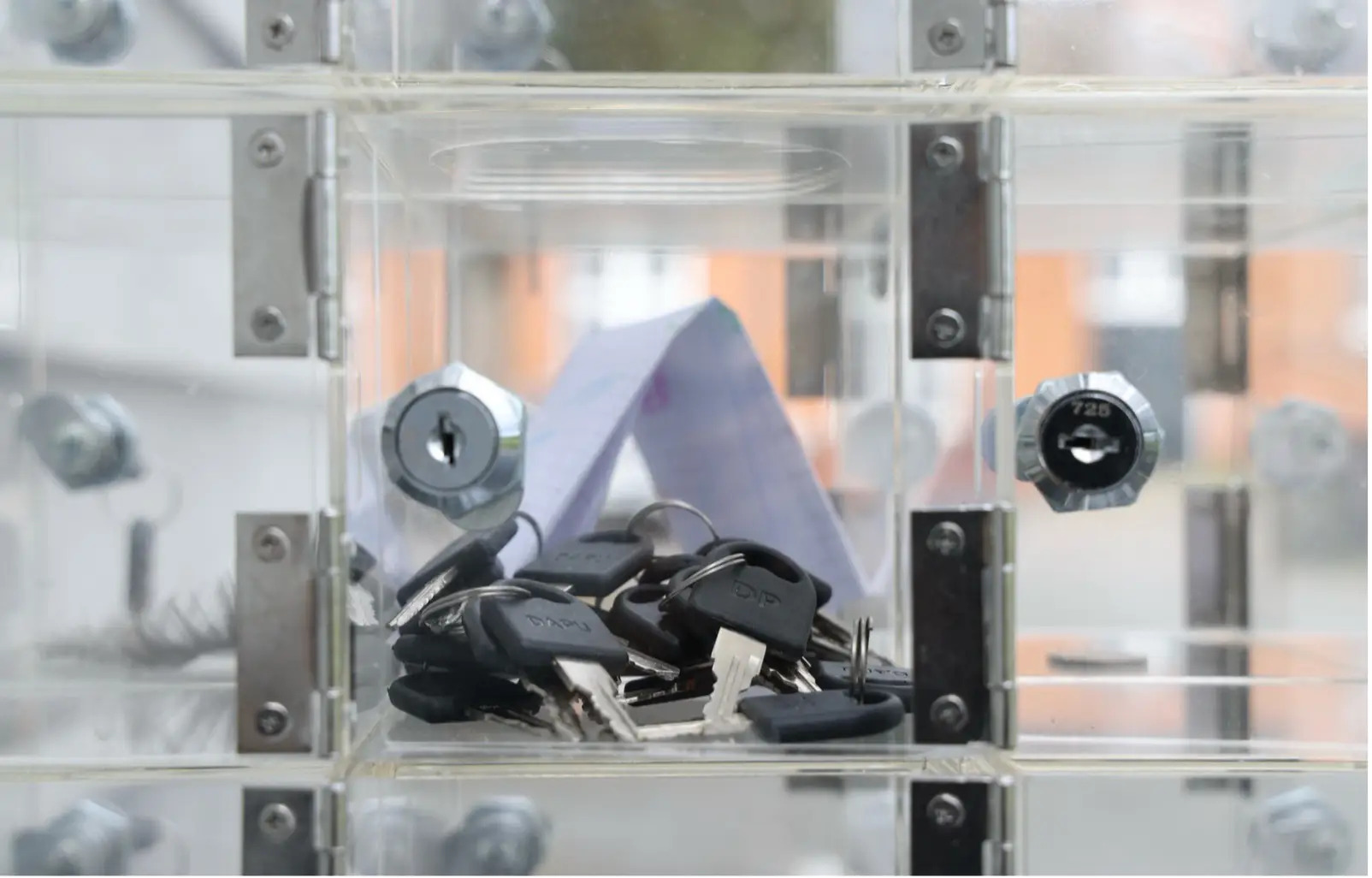

This ongoing inquiry can be found in, for instance, Untitled Collection (2023). In this project, he replaces the singular authority of the artist or curator with a shifting community of participants, each given access to a transparent acrylic cube—a small, seemingly innocuous object that, in Ren’s world, becomes a vessel for agency. Each participant can intervene, fill, curate, or simply leave it be.

As the cubes change, so too does the conceptual shape of the exhibition they belong to. What emerges is not an exhibition in the traditional sense, but a field of possibilities—a porous constellation of intentions and perhaps even misinterpretations. It is not the work that speaks loudest here, but the uncertainty of its framing, the blur of authorship, the refusal of clarity. Haochen Ren asks: Who decides when art begins? And what happens when we no longer recognize its starting point?

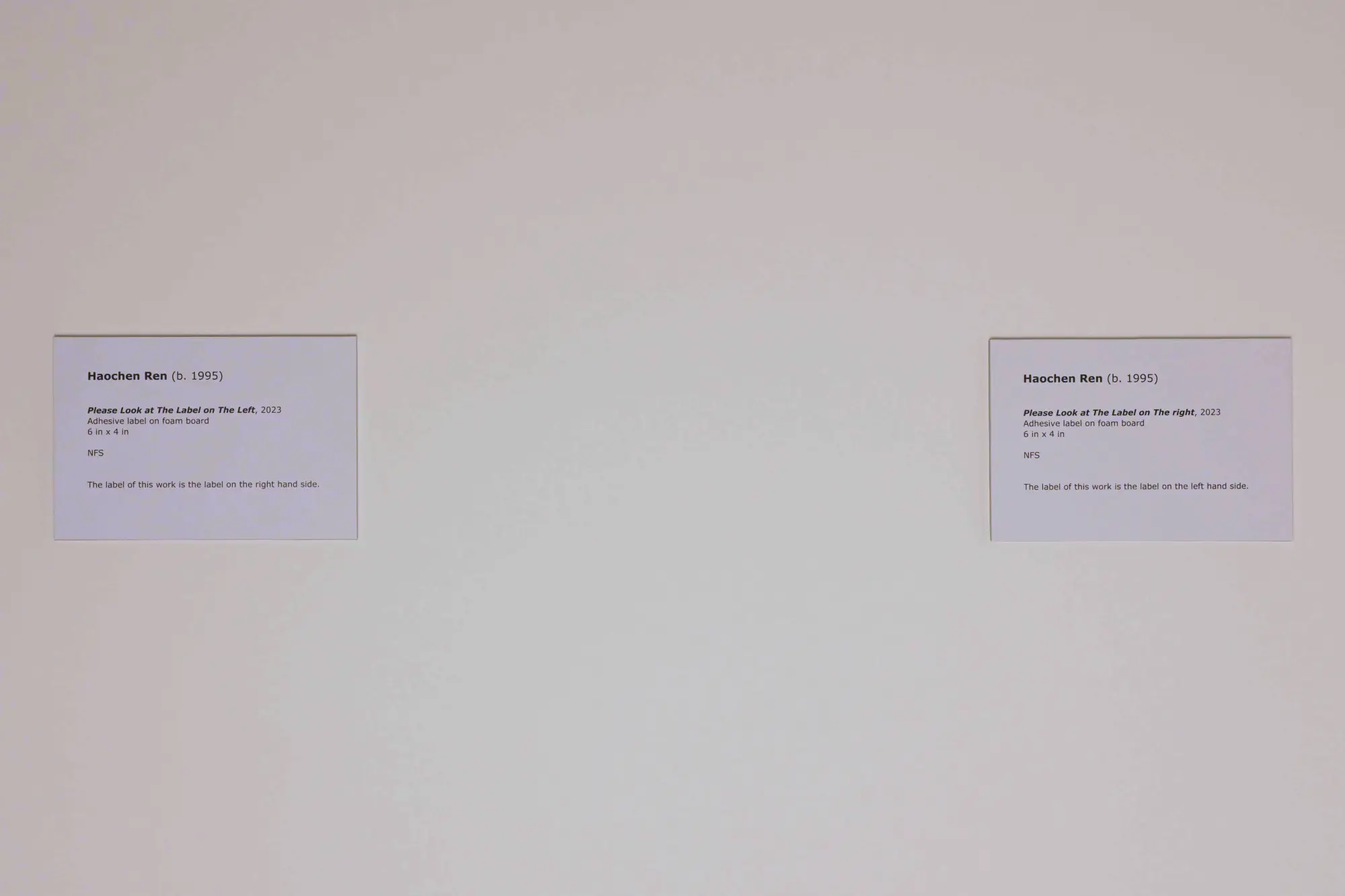

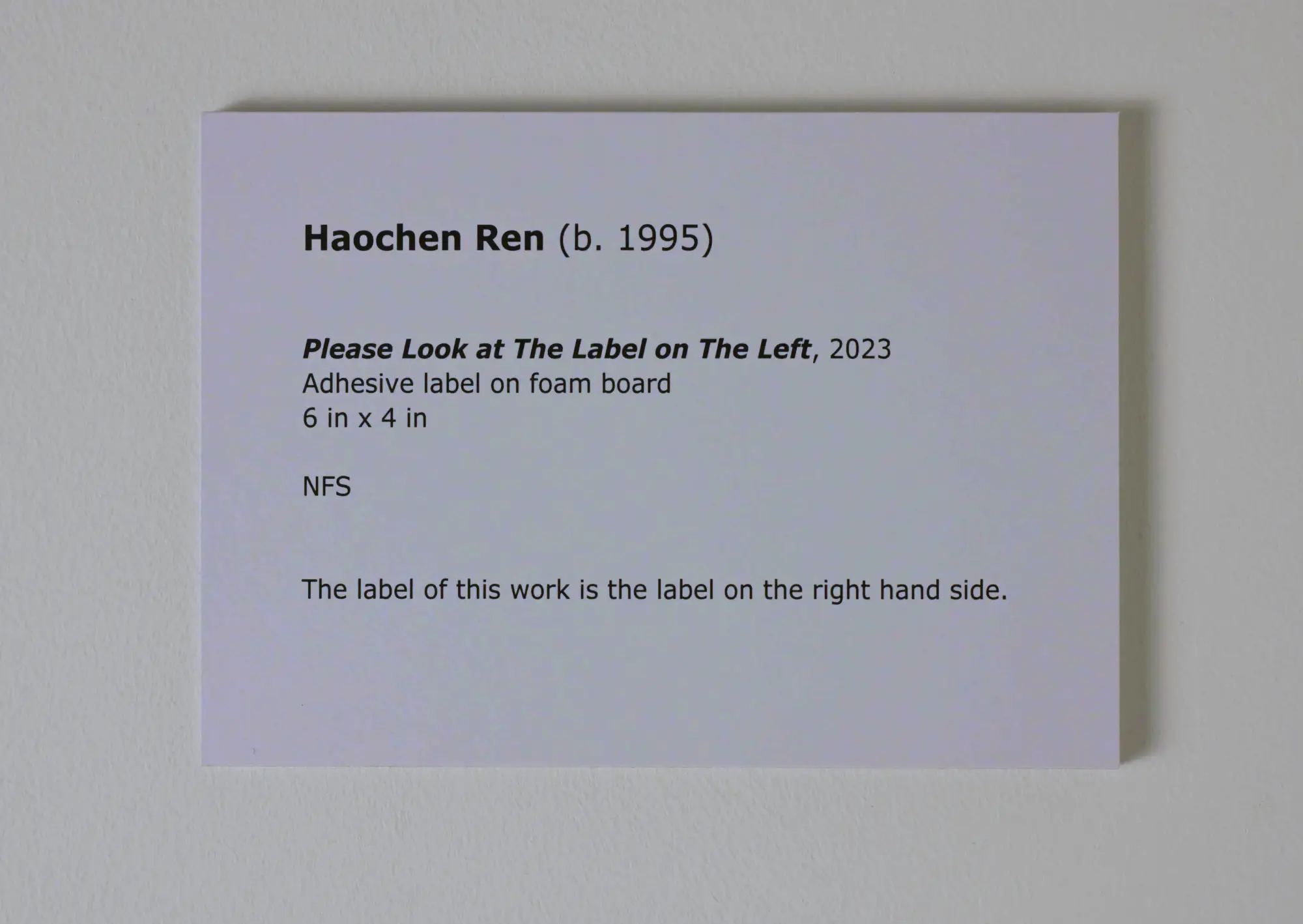

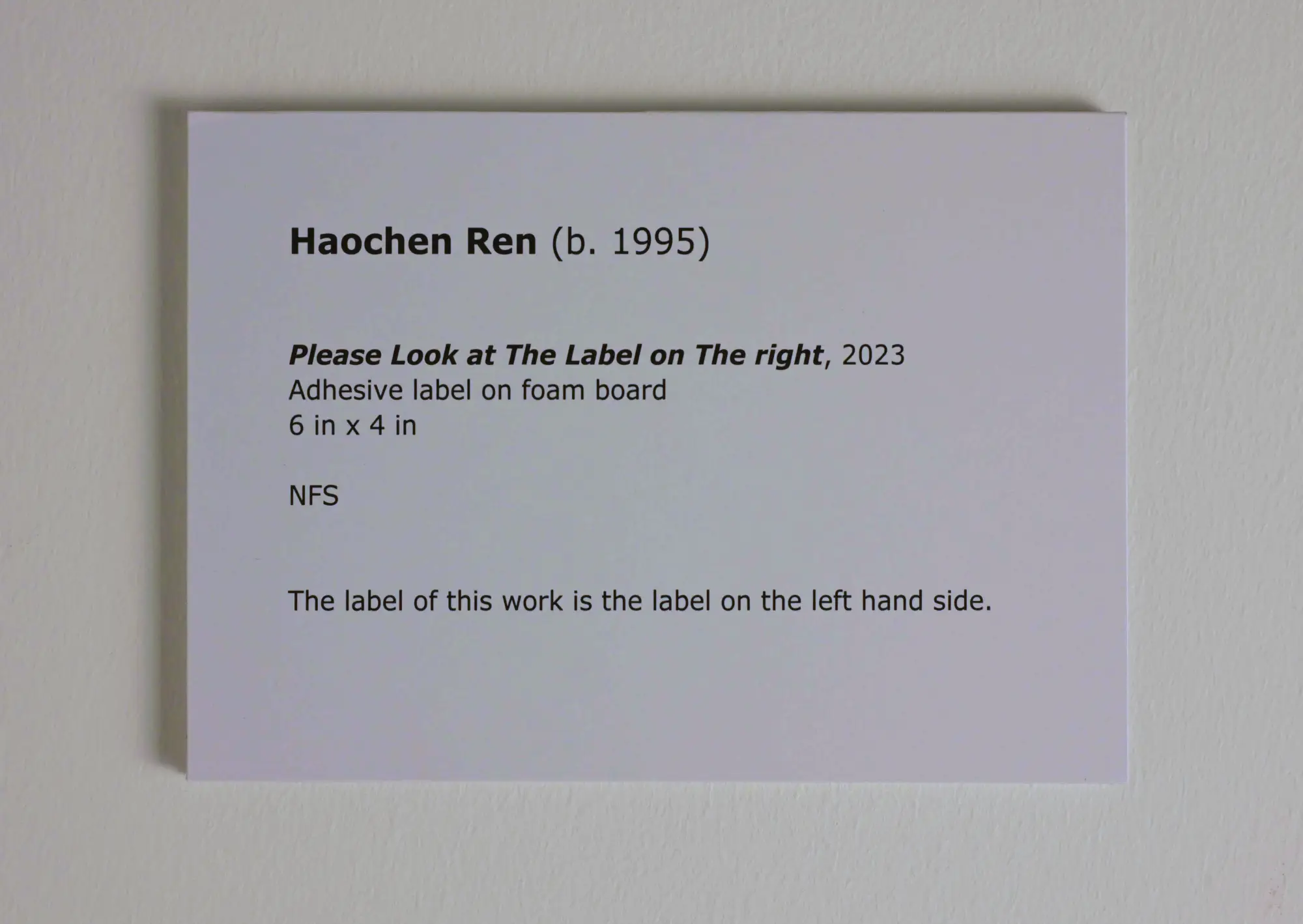

If Untitled Collection disrupts the spatial logic of the exhibition, no title (2023-2025) turns the institutional voice inside out. This series, which has traveled through multiple venues since 2023, centers around a peculiar shift in focus: the gallery label steps into the foreground. Detached from its usual function—of identifying, clarifying, explaining—it becomes autonomous. It floats. It refracts. Haochen Ren’s work does not offer conclusions but are questions disguised as formats. He teems with curiosity and a refusal to settle. He speaks of “the happening of art” with a gentle skepticism, asking: When does it really occur? When does the artist declare it? When does the institution bless it? Or only when the audience completes the circle?

Haochen Ren plays with these labels as if they were metaphysical props. Some point to nothing. Others refer to each other. A few contradict the objects they allegedly describe. The effect is unsettling, and thrilling: the exhibition becomes unstable, each label a door that might open or remain stubbornly shut, depending on how the viewer chooses to read. Yes, the work is almost problematically open-ended, which is the only conclusive reading one can provide, contemplating the label is arguably not a mirror for the metadata, meaning, and value of an artwork, but a mask.

At its strongest, Ren’s practice operates in the register of slow revelation. It resists the acceleration of contemporary attention economies, asking instead for patience—a rare and radical demand. His projects call on the audience to surrender the search for immediate comprehension. Meaning, in Ren’s world, is not delivered. It must be assembled from fragments, from absences, from the slight unease of not knowing exactly where one stands.

There is something quietly profound in Ren’s insistence that the viewer matters—not as a receiver of meaning, but as a co-author. no title does not try to convince you of anything. It gives you the pieces and lets the logic—or illogic—unfold in your mind. Whether the label is a work, or the work is a label, becomes less important than the space of thought that opens in between. One is reminded, reading Haochen Ren’s own reflections, that the art he cares about is not something to be possessed or consumed. It is a way of thinking. A way of pausing. A way of being in a room and realizing that what you thought was certain—the wall, the sign, the rules—are all just soft agreements waiting to be revised.

Haochen Ren describes his exhibitions as “self-examination reports.” It’s an apt metaphor, though perhaps a modest one. His practice often feels more like a kind of quiet spiritual archaeology: gently peeling away the layers of assumption that have gathered around the word “art.” In In Constructing, the gesture is simple but radical—he lends the exhibition space. Not metaphorically, but literally. It is offered, temporarily, to others: to define, to respond to, to make sense of on their own terms. There is something generous, even utopian, in this gesture.

And yet Ren does not romanticize participation. He is careful, almost reverent, about the subtle conditions that make such decentralization possible. He does not offer freedom as spectacle. He cultivates it as a fragile ecology—one that depends on mutual trust, on the viewer’s willingness to think slowly, to move deliberately, to sit with discomfort. And when the space is “returned,” it is not the same. The line between artist and audience has blurred. The exhibition has become, in a sense, self-aware. Its concepts have shifted—not only in the minds of those who engaged with it, but in its very structure. It is no longer a container of meaning. It is a set of relations.

Throughout, Ren remains attuned to the ethics of participation. His exhibitions are never merely exercises in democratic flattening. They acknowledge that true collaboration requires not just permission, but preparation—a cultivation of awareness, humility, and attention. In this, Ren’s work acts less like an open door and more like a threshold: a passage that invites crossing, but does not make the crossing easy or automatic.

Haochen Ren pushes this concept further in The Sky Has Been Temporarily Borrowed for Art. Haochen Ren pushes this further in The Sky Has Been Temporarily Borrowed for Art. A balloon, printed with the work’s title, drifts through the open sky. Spatiality and temporality are no longer stable backdrops; they are borrowed, fleeting materials. The sky itself becomes the exhibition space—unframed, untethered, and available to anyone who happens to look up. The balloon’s quiet flight emphasizes the provisional nature of art’s existence. Where earlier works diffused curatorial authority, here even the physical boundaries of the exhibition dissolve. Art happens briefly, lightly, carried forward by circumstance rather than decree. It asks nothing but attention—and even that, only momentarily.

In another of Haochen Ren’s recent works, he creates a temporary museum to house objects from seafood markets—used kitchen equipment, abandoned and unspectacular. They are not artifacts in the conventional sense, but a shift occurs through Haochen Ren’s minimal interventions of labels—categorically or mentally. Their history is unspoken, their value uncertain, their status undefined. And yet, for one day, they are placed within the logic of exhibition, and thus, momentarily, they become art. This temporary museum does not promise permanence. It does not rely on institutional authority. It suggests instead that perhaps we all possess the capacity to declare meaning, to frame significance. “Everything today is tomorrow’s history,” Ren writes. The question is not what will be remembered, but how we might remember it differently, and who gets to do the remembering.

As a result, Haochen Ren’s work is difficult to categorize. Not because it is opaque, but because it refuses to crystallize. It shifts, like thought, like doubt. It offers no manifesto, no dogma, no solution. Instead, it offers a method of slow thinking, of reconsideration, of stepping back from the machinery of art to look not at its outputs, but at its mechanisms. And yet there is nothing cold or clinical here. Ren’s work is suffused with care. He speaks of “respect,” of “kindness.” These words are clues to the emotional core of a practice that, for all its conceptual rigor, remains deeply human—after all, isn’t art?

Ren’s work succeeds not because it shouts down the structures it critiques, but because it inhabits them from within, quietly shifting their weight. His interventions often feel less like acts of resistance and more like acts of rebalancing, gently reminding the viewer that the authority of institutions is neither absolute nor inevitable. Yet this subtlety is a double-edged sword. It demands a viewer willing to meet it halfway, to engage with its precarious balance between invitation and opacity. Without this willingness, much of the work’s delicate recalibrations risk being overlooked, misread, or flattened into mere aesthetic gestures.

In the end, to encounter Haochen Ren’s art is to be reminded that meaning is not something we find—it is something we make, together. In the spaces between label and wall, between object and viewer, between what is declared and what is simply felt, there is a trembling field of possibility. Haochen Ren does not fill that field. He holds it open. And in doing so, he invites us not only to look at art, but to become part of its unfolding.

Cover image: Detail—Haochen Ren, The Sky Has Been Temporarily Borrowed for Art, s.d. Balloon, air — variable dimensions. Courtesy the artist.

Last Updated on April 30, 2025

- Published on