A Conversation with Alejandro Javaloyas

A Studio Visit During the La BIBI Residency

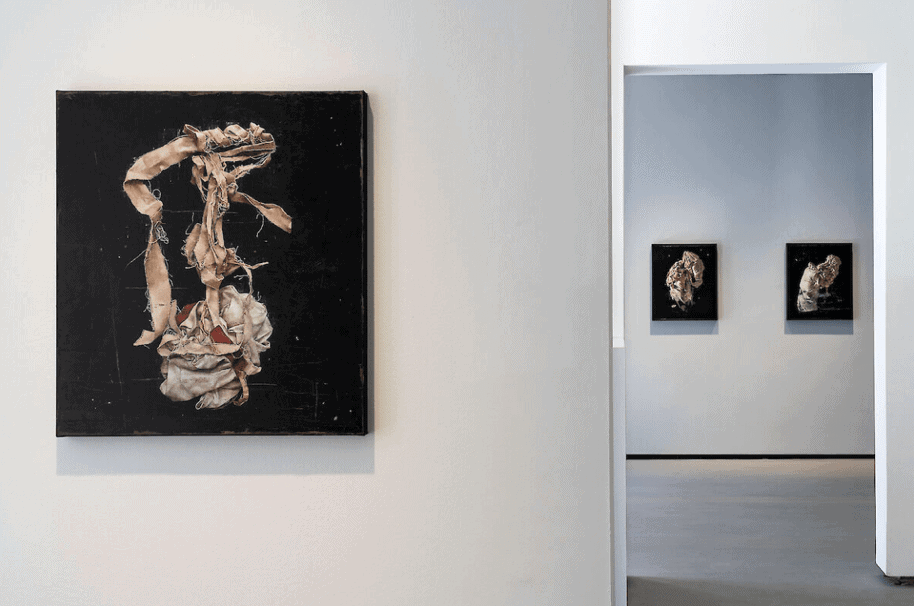

Sebastian Schrader (born in 1978 in Berlin, Germany, living and working in Berlin, Germany) is a contemporary artist best known for his figurative body of works. Primarily painting with oils on canvas, Schraders’ paintings are populated by human figures in an in-between state. The depicted figures seem to be part of a décor as if they have been staged by the German artist in a surreal setting.

JD

Dear Sebastian, thank you for taking the time for an interview on CAI. We are delighted to have you.

SS

The pleasure is all mine—many thanks.

JD

Congratulations on your current show at REITER Berlin titled Useless Light. Could you tell us a bit more about the show and the somewhat surprising title?

SS

The exhibition includes about twelve to fifteen works from the last year. It is dedicated – like all my exhibitions – to painting and its aesthetic manifestation. A recurring motive in this show is the knot-like formations. They appear in different variations. There are figures wrapped in bandages, simple knots, and intricate vegetation. This is the first time I have painted plants and exhibited them as well. The title should give room for speculation, allowing associations and raising questions. In addition, I liked the sound and the mood or connotation connected with it. This incommensurate character of the title embodies a certain melancholy that fits well in the current time. I find the useless, casual, and unintentional very likable, and light interests me anyway.

JD

Indeed, light clearly plays an important role in your work. Over the past five years, the contrast in your paintings has continued to increase, resulting in an impressive claire-obscure as the white draperies seem to float in those indefinite spaces with dark backdrops. The result is an uncanny intensity that has a very direct impact on the viewer. Could you talk us through this play with light and shadow and your overall aesthetics?

SS

Yes, that’s right. I use this spotlighting that creates the chiaroscuro effect. Thereby I am referring to Renaissance and Baroque painting. The harsh light deconstructs the form of the object as fragments are created. This is something very interesting for me. I can use this kind of light to highlight things but also to hide them. The emergence of fragments reveals the loss of unity and the world as a whole. The classic pictorial space does not exist within my work. Basically, I paint an abstract picture. My compositions are more like a Piet Mondrian construction kit. There are surfaces in which forms are clamped. There are structures and textures, contrasts, and rhythms as if composing a song.

JD

What was it that made you paint the way you paint? What incentives urge you to make these images?

SS

It is the result of a long and ongoing process, fed by experiences and certain interests. To list them all would be tiring. Over the years, I’ve wandered through art history and picked up what seemed interesting to me. Those separate elements functioned as building stones, and from all these findings, I built my own house in the end. Further, the confrontation with different opinions was also an important matter. Only when one’s own work is questioned is one forced to think about it. Nevertheless, it is important not to deny oneself. Sometimes I hope that my paintings will answer me. That they would whisper the secret of the world in my ear. So far, they are silent, so I have to continue painting.

JD

What are the main recurring topics throughout your oeuvre? What motives or metaphors are essential? Could you describe the conceptual foundation of your paintings?

SS

I am a bit reluctant towards this conceptual idea. It’s based on sitting down, thinking something up, and then making art. That is perceived as positive, but in my opinion, it overestimates the human mind. For me, art is not a drudgery heavy in content. My goal is not to illustrate my thoughts. I want to create something that is unknown to myself and not limited by my thinking. I have to follow my intuition and give space to the interplay of control and loss of control. There are no certainties. In my opinion, this is also the beauty of art, as a person can be completely human, with all his flaws. This represents a great value because it is a unifying element. I am looking for beauty!

Nevertheless, there are several recurring motives in my work—for example, the question of human existence. Lonely heroes in seemingly senseless situations populate my paintings. Figures that threaten to drown or get entangled in this in-between state. Perhaps this is a feeling that many can share because we live in a time that no longer tolerates continuing like this. Climate change is grasping us, and capitalism is undermining any counter-strategy. We are paralyzed within our systems.

JD

Sadly, there is the issue of the ongoing pandemic, still. In what way did it affect you as an artist, and did it transfer certain developments to your painterly works?

SS

The pandemic hasn’t affected my day-to-day work that much. I’m used to working alone. However, what is interesting for me is how society deals with the pandemic, such as politicians, the people, and even the media. The increasing polarization within society is scary. On certain days, you would think the world is losing it. I also found the multiple reactions of artists mostly disappointing. Too often, an egocentric interest imposes itself on me. The difficulty of finding a social consensus does not bode well for the future. I am pretty sure that the experiences I have gathered will certainly influence my work, but probably more indirectly.

JD

Since 2018-2019, your figures have been covered in draperies, bandages, or cloaked by white garbs. Was this a premeditated decision, or did it occur intuitively?

SS

That was generally intuitive, even if it was, in fact, announced along the way. I had already discovered the piling up of fabrics and garments for myself in earlier paintings. I’m thinking of the Aufgeschoben series (see image below). These mountains of laundry refuse a message on the one hand, and on the other, they satirize it, for there is probably nothing more incidental than a pile of laundry. And yet they embody so many things. It is lying down, for example, or procrastinating, a kind of laziness or the result of perfectionism. In any case, it is a rejection of the meritocracy.

We also encounter these mountains of wrinkles in Frank Gehry’s architecture, who wanted to bring more humanity into cities. The whole history of art is full of loincloths and robes. So it resonates a lot. Formally, it gave me the opportunity to create figurations in which the human being doesn’t actually appear anymore. The figuration transforms into a still life. All that remains is the shell. The denial of a narrative allows the painting to become the center of its manifestation.

JD

How does one read your paintings?

SS

I leave this decision to everyone. When I look at a painting, slowly scanning it with my eyes, it’s a sensual process. I see how the painter approaches his subject and how he deals with his medium. That is, as it were, an approach to the world. Is he cautious, groping, or rabid and haughty? It’s more about the ‘how’ than the ‘what’. I look at the form. In my opinion, it is underrated. People are looking too much for a message, but the medium is the message to bring Marshall McLuhan into play. Of course, the motifs play a role as well, but if I would explain them now, everything would be said.

JD

I have one final question to conclude the interview; you are part of a wider movement in painting, marked by a representational visual language and an often existential or strong psychological emphasis. How do you approach this tendency in painting, and in what manner is it relevant in a contemporary context?

SS

That’s a difficult question. I have not yet perceived myself as part of a movement. But it’s true, there are a number of painters who are pushing a similar visual language. How relevant this movement is is something I can not judge. I think that images spread more quickly through the internet creating certain groups of interest. It remains to be seen how this will affect society on the long term .

I see the bigger trends at the moment in movements like Fridays for Future (international movement of students to fight the climate change), or also in identity politics, which has an effect on culture. This means that the message becomes more important than the form.

JD

Thank you very much for your time and for your paintings, of course. Good luck with the current exhibition and all exhibitions to come. We’ll continue to follow your projects closely!

SS

Thank you for the interesting questions. All the best!

Last Updated on May 2, 2023

A Studio Visit During the La BIBI Residency

A Reasoned Anthology