Zhanyi Chen creates poetic, research-driven works that explore the entangled relationship between sky technologies, environmental systems, and human emotion. Drawing from weather satellite data, early Space Age archives, and soft science fiction, she repurposes technological infrastructures to prioritize feeling over function—revealing how failed or misused systems can become vessels for narrative, grief, and connection.

There are artists who paint what they see, and then there are those who wait for what can’t quite be seen to say something back. Zhanyi Chen is of the second kind. She listens to the sky—not metaphorically, but literally. Her work speaks in a frequency just above hearing, or just below—something like the static you get when a signal’s trying to come through but hasn’t decided what it wants to be yet. As a result, it’s hard to describe what she does without falling into the trap of language that wants to define everything too quickly. Her work isn’t easily pinned down—it floats. It refracts. It mutates. She collects signals, fragments, and archives, and asks what they become when they stop functioning as they were intended.

In a world dominated by technologies that map, measure, predict, and surveil, Chen interrupts. She pulls gently at their seams, not to destroy them, but to listen to the small emotions leaking out from the corners: loneliness, awe, grief, hope. Her fascination with the sky can be seen as a zone of collision between politics and weather, satellites and longing. She once received image signals from a Russian weather satellite—those ghostly transmissions filled with static and trace. That moment, of watching data arrive from a machine thousands of kilometers away, seems to have lodged something permanent in her work: a sense that all communication is haunted. That our attempts to reach out—to machines, to the dead, to the past, to the clouds—are always tinged with the possibility of failure. Or maybe something better: a failure that opens into poetry.

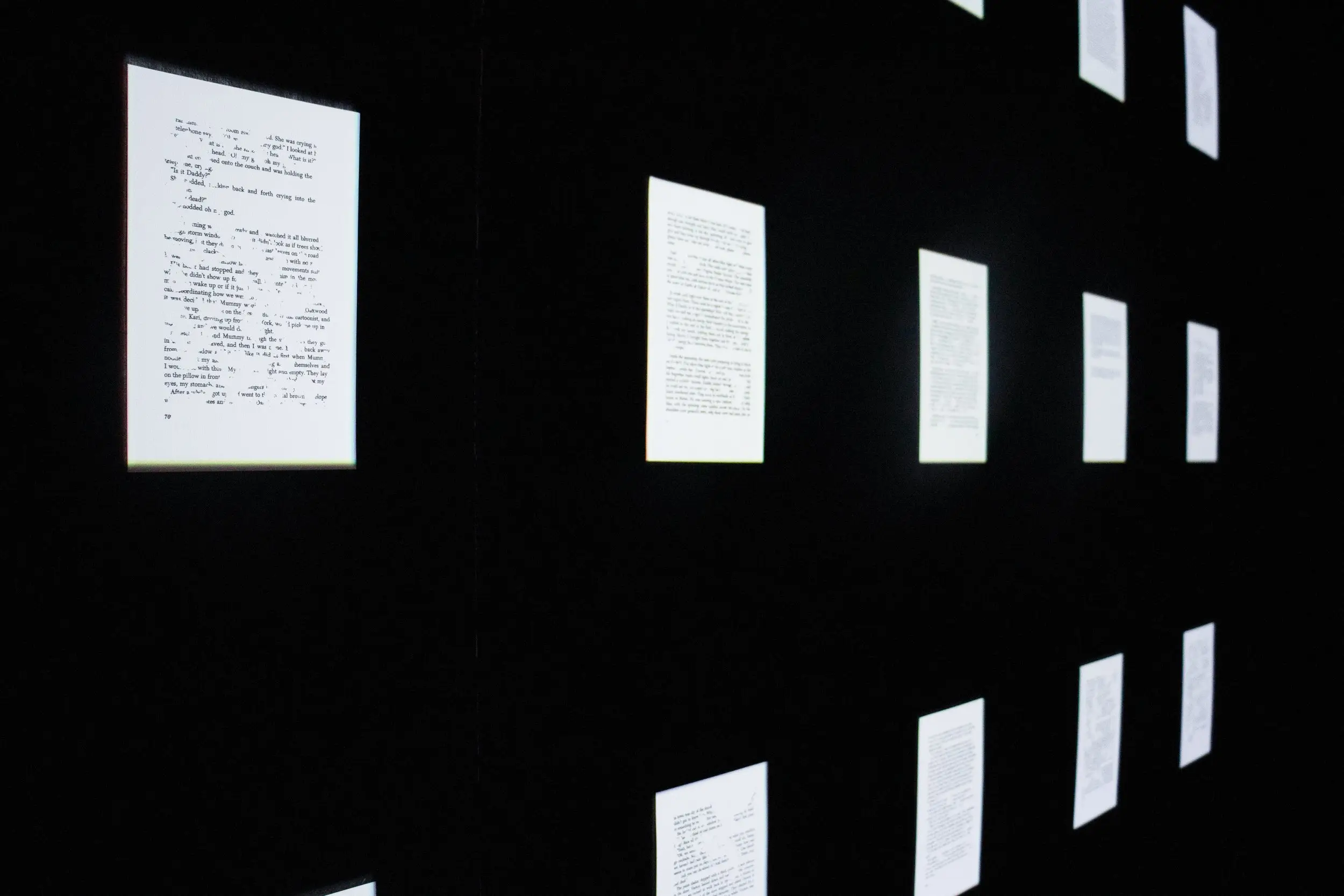

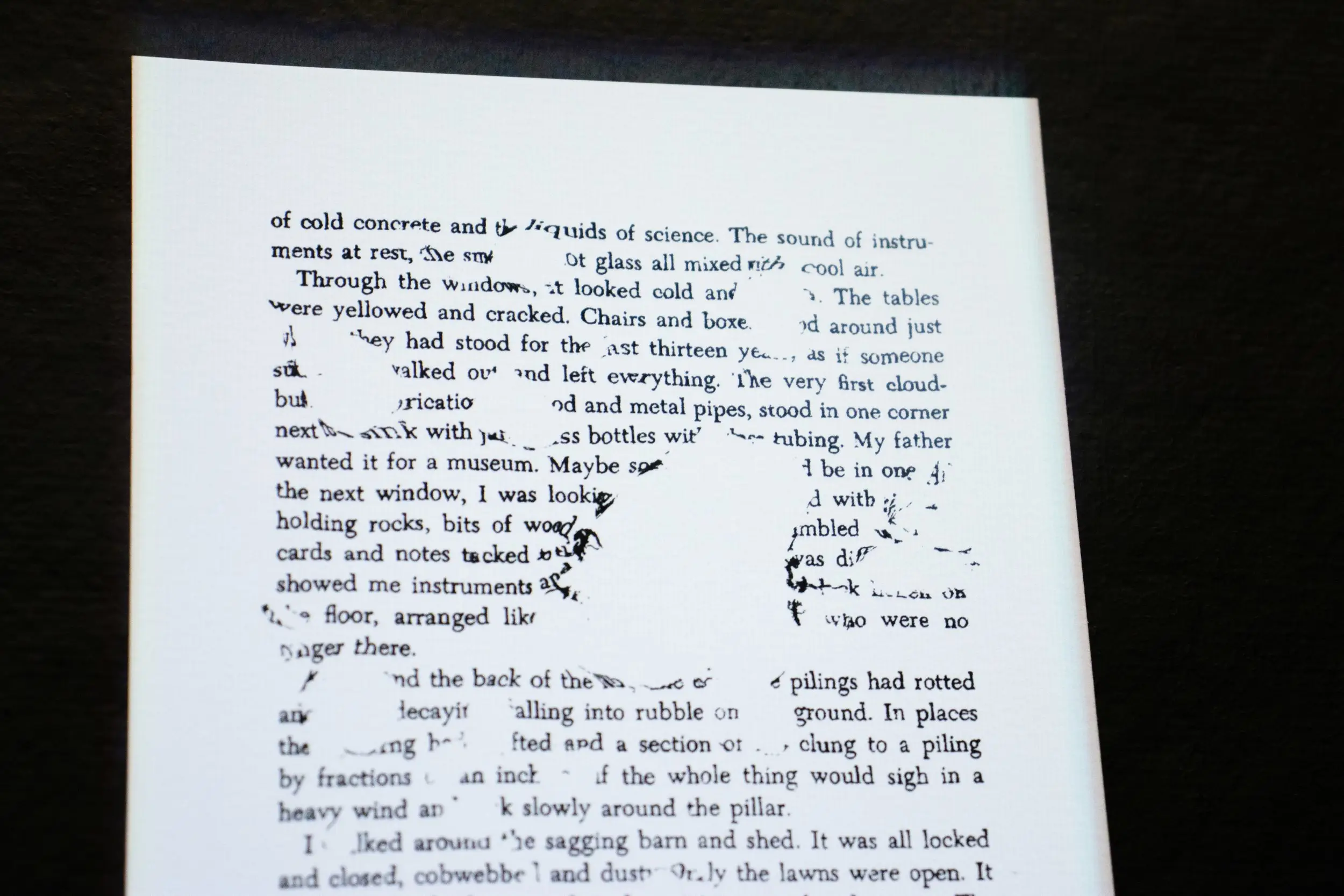

For instance, in Cloudbusting (Rain Poems) (2024), she doesn’t write the poem, but the rain does. Peter Reich’s words, lifted from his childhood memories of cloudbusting with his father, are printed onto water-transfer paper and left out in the weather. Rain chooses which words to keep and which ones to blur into disappearance. It’s a kind of collaboration between human grief and natural randomness. The resulting texts don’t make sense in the traditional way—there’s no sentence to follow, no conclusion to draw. They read like memory feels: partial, dissolved, persistent. What’s left is something that resists being read and insists on being felt. The rain becomes a medium in the spiritualist sense—a presence that tries, clumsily, to speak. The attempt matters more than the outcome. There’s something quietly devastating about that. You don’t read Cloudbusting to understand, you read it to remember what it feels like to want something back that cannot return. The poetry is not in the words, but in the space where words begin to fail.

That space—between technology and emotion, between data and dream—is where Chen builds most of her work. In Tele-Sky Unplugged (2023), she revisits Aldo Tambellini’s 1981 Tele-Sky, but removes all the electronics. The CRT television casing remains, but the screen no longer shows pixelated skies beamed from distant lands. Instead, it reflects the actual sky above the viewer in real time, using only a mirror and a lens. No wires. No signals. No processing. It’s a kind of unplugging not just from the machine, but from the logic behind it—the Cold War telepresence fantasy, the idea of connecting continents through satellites. Instead of a technological marvel, we get a stillness. A reorientation. The sky returns as itself, not as a mediated spectacle.

But it’s not naïve. Chen knows that even this reflection is charged—with memory, with history, with ideology. The casing still speaks. The past hums inside the plastic. The piece becomes a quiet conversation across time, between artists who looked up at the same sky, but through different lenses, between an era of conquest and an era of collapse. Both Cloudbusting and Tele-Sky Unplugged suggest a kind of unlearning. A loosening of what media is supposed to do. A willingness to let the weather interrupt the narrative. To let distance and distortion become part of the message. For Chen, malfunction isn’t a problem but an opening. Even the titles of her works feel like fragments of stories you’re only catching the tail end of. They’re long, delicate, sometimes a little absurd.

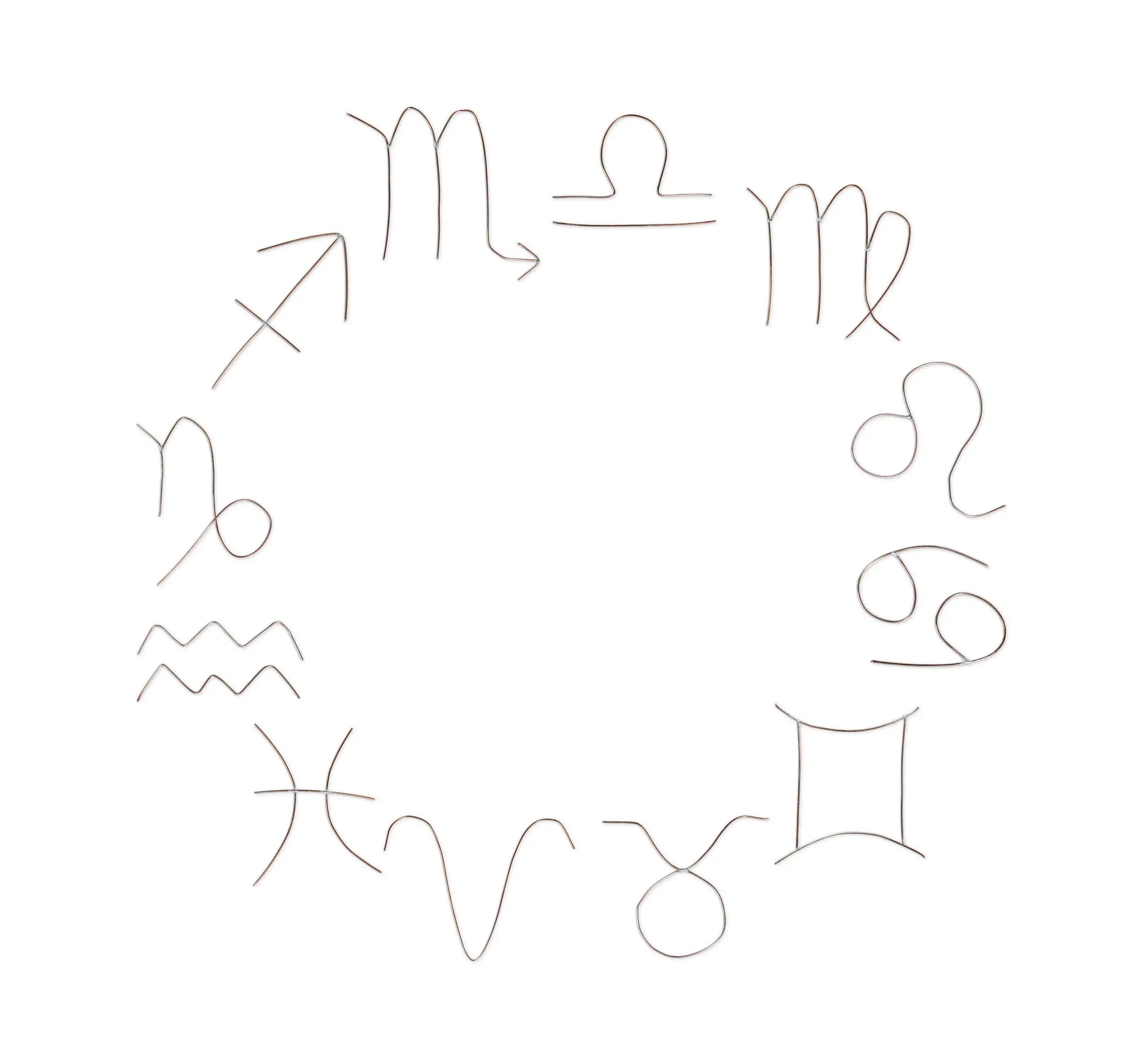

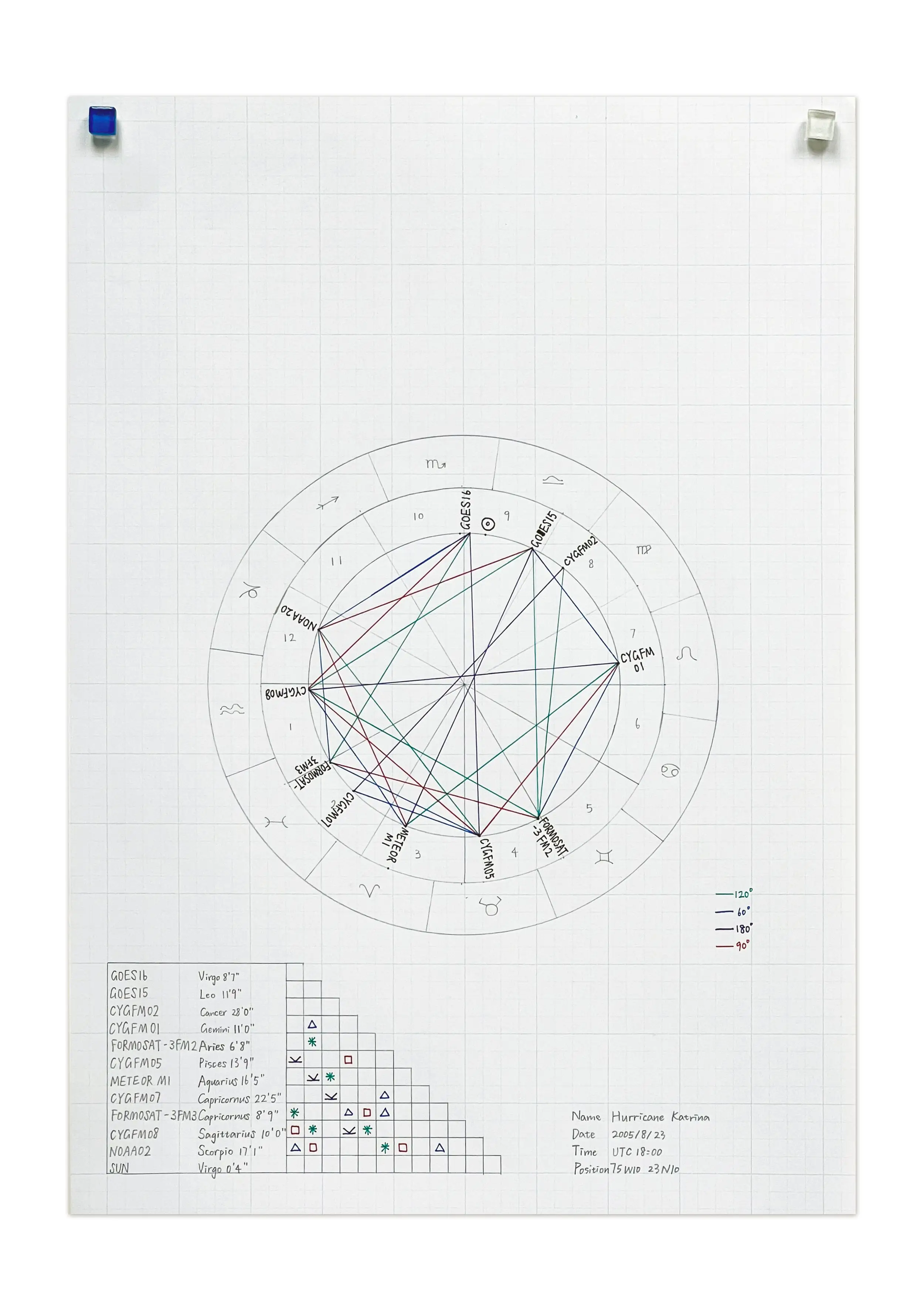

Elsewhere, in Artificial Satellite Astrology (2023), Chen leans into the absurd with a kind of reverence. She reimagines the machinery of satellite networks not as tools of surveillance or communication, but as celestial bodies guiding horoscopes. Antennas are repurposed to receive divinatory signals, while a fictional YouTube channel offers tutorials in this new astrology. It’s funny, yes—but not a mockery. In the absence of cosmic mysticism, we reach for something human: connection, narrative, the comfort of symbols. The suggestion is not that we believe, but that we want to. And that want is enough to make meaning matter. Across all her works, Chen doesn’t critique technology so much as reorient it. She misuses it with tenderness. She lets it fail. And in the gaps where function slips, feeling rushes in. You carry it with you like a static signal still buzzing somewhere, half-decoded or half-forgotten.

Born in 1997 in China, Zhanyi Chen holds an MS in Art from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the United States of America, and an MFA in Digital + Media from the Rhode Island School of Design, the United States of America. Notable exhibitions include presentations at the Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art, MA, the United States of America; the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai, China; the MIT Museum in Cambridge, the United States of America; and was a recipient of the Harold and Arlene Schnitzer Prize in the Visual Arts. For more information, please visit the artist’s website here.

Last Updated on May 21, 2025

- Published on