A Conversation with Alejandro Javaloyas

A Studio Visit During the La BIBI Residency

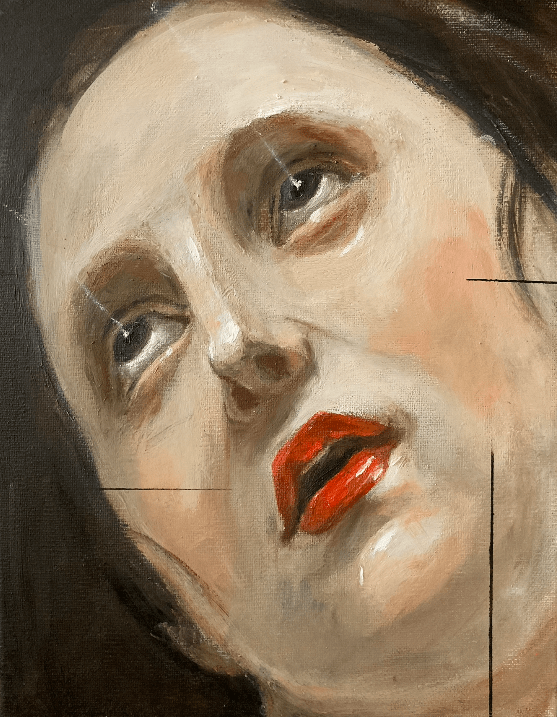

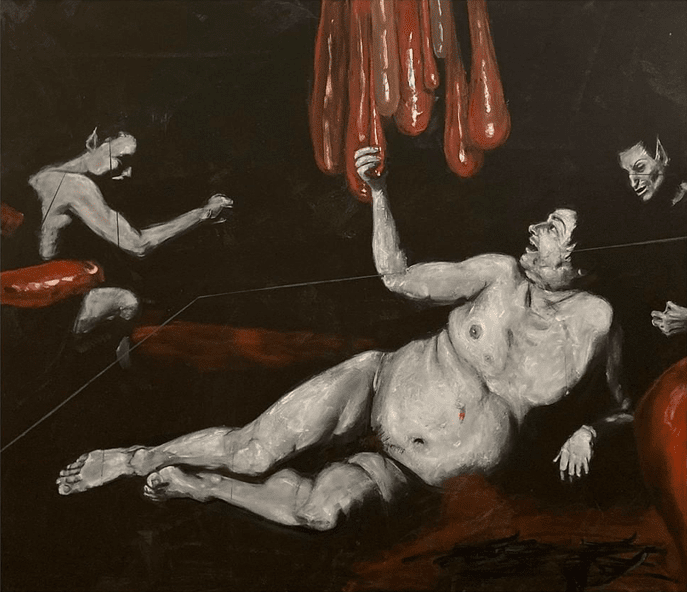

Victor Paukstelis (born in 1983, resides and works in Vilnius, Lithuania) is a contemporary painter who is best known for his ingenious compositions of iconic imagery juxtaposed with surreal, conceptual, or personal elements. Paukstelis’ paintings escape from being drowned in today’s flood of images. They trigger familiar structures, borrowing items from our collective memory, before altering—or even disturbing—them, resulting in an ongoing tension embedded in his masterly brushstrokes.

JD

Dear Victor, what a pleasure it is to have you on CAI for a conversation on your works. Welcome. How have you been?

VP

Dear Julien, I’m a regular follower and admirer of CAI’s work, so I’m very happy to be able to talk to you. I’m doing well! I’m trying not to succumb to the darkness of Lithuanian winter, and I’m working on new paintings.

JD

Sounds very interesting; looking forward to discovering your latest works, and thank your appreciative words. The past two years have been eventful, to say the least, troubled by Covid and all that has come with it. I have noticed many creative minds enjoyed the isolation, which is something that seems to come naturally for an artist. What effect did Covid have on you personally? You often incorporate personal experiences or memories into your works. Is this a pathway for Covid to enter your works?

VP

I sometimes ask myself whether an easy, comfortable life makes it easier to create good art or, on the contrary, it encourages superficial, entertaining, imitating art. Often, both personal and social shocks force the artist to step out of one’s comfort zone and create something deeper and more original (but, of course, this is not always the case).

Quite often, the artist who seems to have it all still experiences constant inner anxiety because the creative process is usually unsuccessful without it. When I create, I’m surprised that I never manage to follow the same path, and I constantly enter new zones of creative discomfort. Every new work starts as if from scratch, from a blank canvas. For me personally, this was a creative and productive time. I think that societal anxiety was still reflected in my work, even indirectly. I wouldn’t say that the topic of Covid is explicitly employed in my new work, but there is a subconscious influence.

JD

The past two years have also been very successful for you personally. For instance, your works have been collected by the Modern Art Centre (Mo Museum) in Vilnius and by the Lewben Art Foundation in Vilnius. You have also had breakthrough moments with shows abroad, traveling with your works to Austria, the United States of America, Canada, Germany, and Sweden. Where did your career as a painter start? What was your road to artistry?

VP

My journey as a professional painter began in my early 30s. As a child, I was trained as a classical pianist. Later, I performed as a pianist a lot. I applied to the Vilnius Academy of Arts when I was already 30. I studied there for six years. But all my life, I’ve been painting and drawing as an amateur without any special training. I guess it was and, in a way, still is my vocation.

My mother, whom I lost a year ago, also grew up in a family of musicians and later taught piano. She wanted to make visual art all her life but never made her dream come true. I’ve inherited her dream, so to speak, and I’m making it come true. In her childhood and youth during Soviet times, my mother used to plaster a huge wall in her house with photos of artwork cut out from art and other magazines. I have been looking and fantasizing about those cut-outs in my grandmother’s house since I was a child.

That wall is still there, but it has faded a lot with time. It was probably by looking at my mother’s art albums and observing that wall that I started my journey as a visual artist. I’m very glad that institutions, such as Mo Museum and Lewben Art Foundation, exist in Lithuania and that they collect contemporary art because we don’t have a long tradition of collecting and sponsoring art, which is common in Western countries.

JD

I am sorry for your loss. What a terrific and valuable anecdote. Could you talk us through your creative process? Often, the starting point for your paintings is an existing image ‘borrowed’ from art history or from the collective memory.

VP

The history of art and painting is indeed very important in my work. Often, an existing painting becomes the first impulse at the beginning of the work. I start by looking for an image that hypnotizes me. When I find such an image, I try to figure out the reasons for this hypnotizing effect. In a way, the idea develops in the process of painting. I really like the feeling that I’m not in control of the painting process, but vice versa; it is in control of me.

I don’t remember which painter said that painting is like snowboarding at high speed down a mountain because you never know what’s around the corner. For me, painting is even more like running a marathon because to do it, you have to reach a so-called flow state, where you almost lose consciousness and must balance between rationality and senses or intuition.

JD

I recall reading in our artist spotlight on your works that the audience experiences a sort of déjà vu due to these ‘borrowed’ images. Yet, at the same time, you aim to disconnect or distort the image through painterly interventions, creating a visual or conceptual conflict. Does this déjà vu moment evoke a certain state of accessibility for the viewer? As if we are confronted with the memory of an image that’s been blurred, as if oblivion is slowly but surely setting in?

VP

The very age we live in is such that the borrowing or appropriation of images is inevitable for most contemporary artists. The boundary between what is one’s own and what is borrowed has almost disappeared. The most famous painters and the best film directors use images they have already seen, incorporating elements of déjà vu.

Painters admire and adore bygone epochs and kneel before masterpieces. The question is whether it reflects a certain lack of originality in society and in the art world—maybe it has always been this way—or whether it is more of a transition period to a new era. Maybe we live in a period of postmodernism’s last gasp.

JD

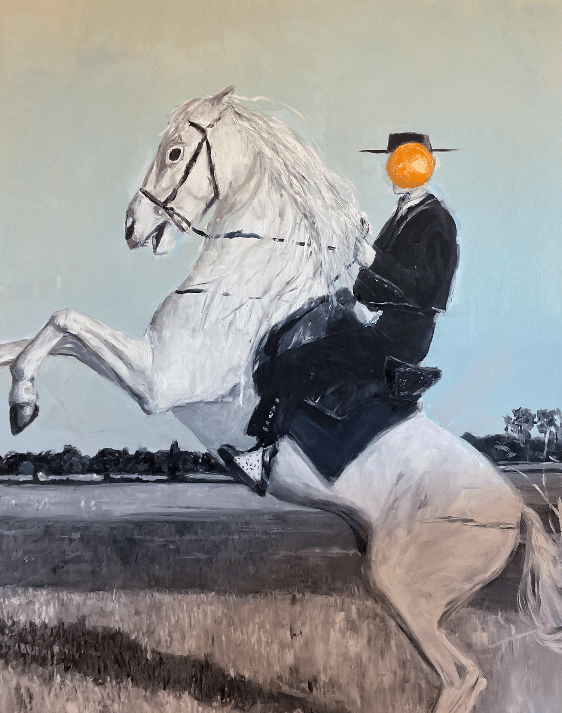

I agree strongly on this matter. With recent writings on post-postmodernism, trans-postmodernism, and metamodernism, one definitely senses a shift in tone and in form. A characteristic motive in your oeuvre is the surreal implementation of oranges floating inside the picture plane. Could you describe its function, your intention, or the desired effect of these oranges?

VP

I vaguely remember a story I read when I visited Turner’s exhibition at the Tate Gallery. The artist had placed a pumpkin in a landscape, and when his friend asked him why he did this, Turner said that he simply needed a warm color accent in a landscape of rather cold tones. The pumpkin was the most appropriate in terms of size, shape, and color. Turner was simply trying to solve a painting problem.

In my case, it is not so straightforward. First, I want to introduce color accents into monochrome painting. Second, I combine the traditional landscape painting genre with still-life elements. Third, I want to bring a touch of humor to the rather serious, sometimes even desperate, character of my paintings.

As one painter put it, “Every good work of art must have at least a drop of humor.” The same probably applies to life because otherwise, it would be very difficult.

JD

There is also a very tangible conflict between the original image’s source and the intervention’s source. Whereas we find the main composition or source material in our collective memory, the intervention is often a result of personal memorabilia. How does your works’ tension between the collective and the individual memory unfold?

VP

It would be difficult for me to distinguish what belongs to the collective memory and what belongs to the individual memory in my work, especially during the creative process. When I paint, I simply follow the image and just strive to paint a more convincing painting for myself each time. Painting is unique in that every time you paint, you dive deeper and see that there are no limits, both in terms of ideas and craftsmanship. I paint things that move me and are important to me at the time. They naturally draw on both collective and personal memory.

JD

We encounter the likes of Michelangelo, Diego Velàzquez, Édouard Manet, or Caravaggio in your works, but also Richard Wagner, taxidermy, birds, football players, and more. Even though there is an amalgam of historical eras, your works seem to be characterized by a strong continuity. Is it the continuity of an anachronism, or are the interventions a binding factor for any era?

VP

I must be working in a similar way my mother worked when she used to put cut-outs on the wall. She had to match one cut-out to another to make a whole, and I needed different themes to create. There are painters for whom one genre is enough. In my case, I’m always looking for motifs that open painting in a new way for me and bring new tasks and possibilities. Like a film director, for example, Stanley Kubrick, I move from the historical plot to the fantastic, then to horror, and so on. For me, it is very important not to repeat myself and not to become my own stuffed animal.

JD

What can we expect in the coming years from you? Are there any upcoming projects you could share with us?

VP

I’m currently working in my studio in Vilnius, which is in an old Tsar and Soviet-era prison that has been closed for a few years. The studio is in what used to be a Catholic chapel. It has a special aura – a mixture of awe, mystery, and hope. I am working on a series of new works there. I plan to show them in an exhibition next April.

JD

Sounds like a truly terrific studio location. In any case, we are strongly looking forward to your upcoming works and exhibitions. Thank you for your valuable time and intriguing answers. It has been a true pleasure. We’ll stay in touch for sure. Thanks!

VP

Thank you very much for your interesting and meaningful questions. Best of luck!

Last Updated on August 1, 2023

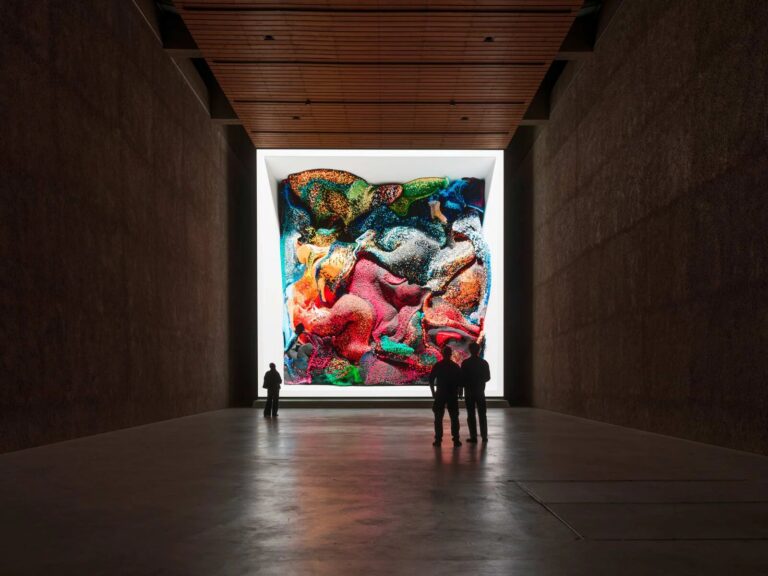

A Studio Visit During the La BIBI Residency

A Reasoned Anthology