Brigitte Kowanz: Remember the Future

Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna, AT

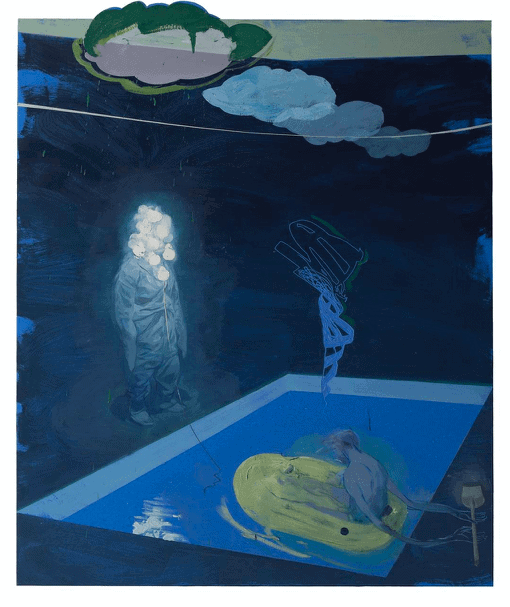

Ruprecht von Kaufmann, born in 1974 in Munich, is a contemporary painter living and working in Berlin, Germany. Von Kaufmann achieved international recognition with his figurative body of works, mainly consisting of oil paintings on linoleum and charcoal drawings on paper. The German artist distinguishes himself from the bulk of contemporary figurative painters with his dynamic touch and unique color palette. Strongly marked by an edge of surrealism and the absurd, von Kaufmann populates interiors and landscapes with figures. Drawing inspiration from daily life as a comment on reality, evoking intriguing narratives and captivating images.

JD

First and foremost, welcome to CAI. Thank you for taking the time for this interview.

RVK

My pleasure!

JD

I can only start this conversation by congratulating you on your most recent monographic publication, Ruprecht von Kaufmann: 2013 – 2020. Almost a retrospective in print, a true landmark for any artist. Could you talk us through the catalog?

RVK

In 2013 I discovered linoleum for myself as a painting ground. Just before that, I pushed my painting in a new direction, simplifying the backgrounds and leaving some of the underlying drawings visible in the finished painting. The paintings became rougher and more sketch-like, but at the same time – I felt – more to the point and more impactful. The strange thing about this kind of change was that I had been striving to push my work in that kind of direction for a while, and then all of a sudden, this door opened, and all I needed to do was walk through it.

In 2018 when I first started thinking about a new book, it seemed very important to document these crucial shifts, to give those, for me, very pivotal works a platform. So that’s why it has some retrospective qualities. In discussion with my wife – who is incredibly supportive of what I do and who has designed the book – we came up with the idea of not showing the works in chronological order but restructuring them into overlying themes that tie very different pieces from different years together. Even though the publisher was skeptical at first, I am very happy we went that way. It makes the book more lively and interesting to read. Sylvia Volz did an incredible job with the very difficult task of tying it all together in her text. I think it is a very important invitation into the world the paintings encompass.

The pandemic nearly choked the project. My gallery – Gallery Thomas Fuchs in Stuttgart – who has co-financed the book, was really uncertain if we should go through with it in an unpredictable year like 2020. Fortunately, two museums, the city-owned Gallery at Gutshaus Steglitz in Berlin and the Buchheim Museum near Munich, offered me solo shows at around the same time, and with that came some financial support from their end. That finally got the project off the ground. A book like this is a collaborative effort that I couldn’t have realized without the support of a whole host of people. Too many to name them all here!

JD

Monographs or retrospective shows are often key moments for artists to reflect on their work. Does the monograph have an effect on your artistic practice or direction?

RVK

Not really, to be honest. I have never been much of a looking-back kind of guy. It’s like mountain climbing. The last climb isn’t of any importance—only the next one counts. For me, it’s the same with paintings.

And at the same time, yes, a book like this is great because it reminds you of what you have done with your life for the past couple of years. But for me, changes and the continuous evolution of my work have always been essential. If I would just repeat what I have been doing before, I might as well be working in any other job. What is so fantastic about being an artist is that every painting wants something different, something new from you.

Today I am forcing myself to make shifts and changes more gradually because I learned over the years that collectors, galleries, and art critics don’t follow along as quickly. You need to give them time to catch on and lead them along with your thinking. Several times, I have lost almost all of my collectors and had to build up a new collector base because many just didn’t like the direction I was taking with my work. That’s just part of the job.

JD

The book compiles your work from 2013 up to 2020. Would you say there is a visible development?

RVK

Absolutely, I would say so. As I have mentioned before, 2013 brought huge shifts in my work, and the first paintings in the book are still painted on canvas. And then, you can see the process of how I explored different routes and avenues that the changes in material and in thinking offered. One of my heroes is Beck (the musician). I love how, with his albums, you never know what you will get in the next one. The only thing you can rely on is that it will be different. So in the book, you probably won’t read through it, and like every painting. But maybe, and hopefully, you will grow to understand and love some of the ones that you didn’t connect with at first.

Unfortunately, the book doesn’t include the smaller works; they often are my experimentation ground and could have filled in some of the steps in between larger works. But it would have gotten too extensive. So maybe there will be another book with just the smaller format works in the future.

JD

As you have mentioned, sadly, there still is the issue of Covid. How did you experience the pandemic, and in what manner did it have an effect on you or your work?

RVK

The pandemic has been a mixed experience. Partly, I enjoy the slow pace because it allows me to spend more time painting and less time organizing exhibitions. It also has led me to think about other avenues more, like maybe getting back into teaching as well. I love teaching, but it’s also such a time drain. But Covid has got me thinking about that again.

Then there are all the concealed shows and the canceled fairs. I have an exhibition in the City Gallery Gutshaus Steglitz in Berlin right now. But no one can see it. That’s a really sad experience. And even though I am used to less social contact than most people, I am starting to feel the strain of social isolation. But I try not to worry too much and focus on what’s ahead and how to keep going. So far, my galleries have been doing great work to power through the pandemic. But really, I am most worried for my kids right now. They have more or less lost an entire year of schooling and companionship. For them, it’s been really rough. All of that might creep into my paintings eventually. It usually takes a little while for current experiences to filter through memory and be reassembled into ideas for paintings.

JD

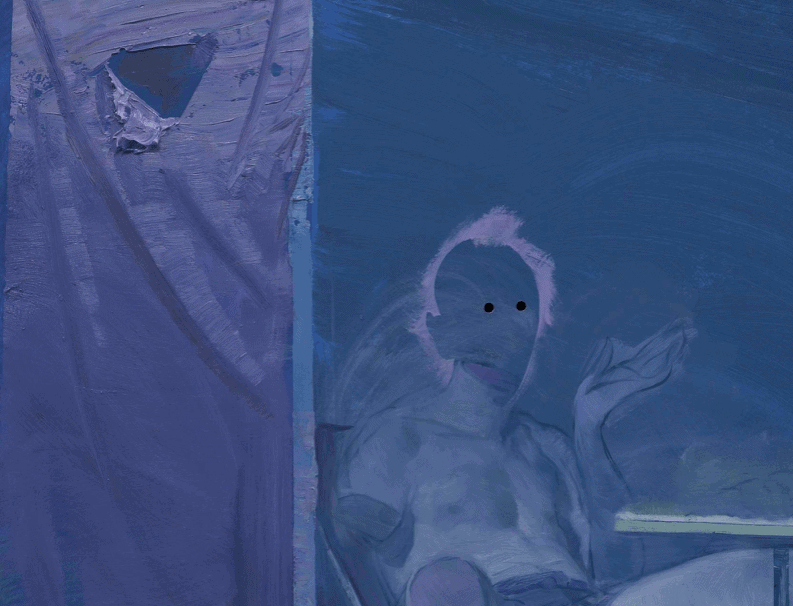

A recurring characteristic throughout this body of works of seven years of painting is the implicit absence of faces. It was blurred, evaded, hidden, destroyed with a strong impasto, or sometimes not painted. How did this strategy come about, and why?

RVK

I want the people in my paintings not to be a specific person but a specific type of person. So I am consciously avoiding ‘portraits’ in my paintings. For me, a painting becomes alive through the viewer who encounters the image later on. And for the viewer, it becomes possible to make the painting their own if they recognize figures from their own life experience. So I try to leave the figures as open as possible while being as specific as necessary.

JD

The implementation of this image formula has been increasingly visible over the past two decades. What’s your viewing point on this matter? Why do we feel so strongly not to paint faces and/or view pictures without faces?

RVK

We make connections with another person through the face. We think we can ‘read’ others through their eyes. We also think that emotions are transported through the expressions on a face. But if those clues are missing, we are being thrown back onto ourselves. We intuitively empathize with emotions that are communicated through posture and body language. This reaction is much more subtle. It’s like a riptide that pulls us under and into the painting when the surface looks harmless and quiet. But then your own emotions are being triggered. I want the viewer to have a strong emotional response to my paintings.

JD

Does painting itself sometimes demand to blur or hide the faces?

RVK

Blurring or erasing is a regular part of my painting practice. I want the paintings to have a certain rawness and fluidity that would get lost if I labored too much over a certain section. So I often take a scraper, scratch out hole areas when I feel they have gotten too tight and too precise, and then work back into the remnants of what was there before. That process of destroying and rebuilding can go on for quite a while. I want the failures still to be visible. To me, the figures look more believable that way because they are themselves flawed, like actual human beings. But leaving mistakes visible also allows a presence of vulnerability on my end. A true connection is only possible when you allow yourself to be vulnerable. And I want the paintings to connect with their audience.

JD

As a painter, one could argue you are a painter who paints from the heart. What role does intuition have in your creative process?

RVK

Intuition is always a very essential part of the painting process. That’s what differentiates painting from Conceptual Art. The painting process is a continuous series of sometimes incremental decisions. Of course, some of these decisions, usually the drastic and more dramatic ones, are well-planned and thought out. But to brush over the many, many minor decisions you take without a conscious thought process would be greatly undervaluing their importance, like driving a car down a road. Yes, you think about it when you need to take a turn. But a large part of the driving process happens subconsciously.

But most importantly, don’t underestimate failures and happy mistakes. They can’t be calculated and anticipated. But when they happen, they sometimes dictate a new direction that you hadn’t thought of starting out. Sometimes they crystallize an idea and help you to be more precise. That’s what people used to call ‘a muse’ in the old days, I presume. It can happen that a painting takes control and tells you exactly what it needs. And then it’s my role to step back and follow that lead. I find that this usually results in a better painting than I could have hoped for. So it’s a process that is just as much intuition as it is planning and conceptual thinking. And experience makes the borders between the two more and more blurry and permeable.

JD

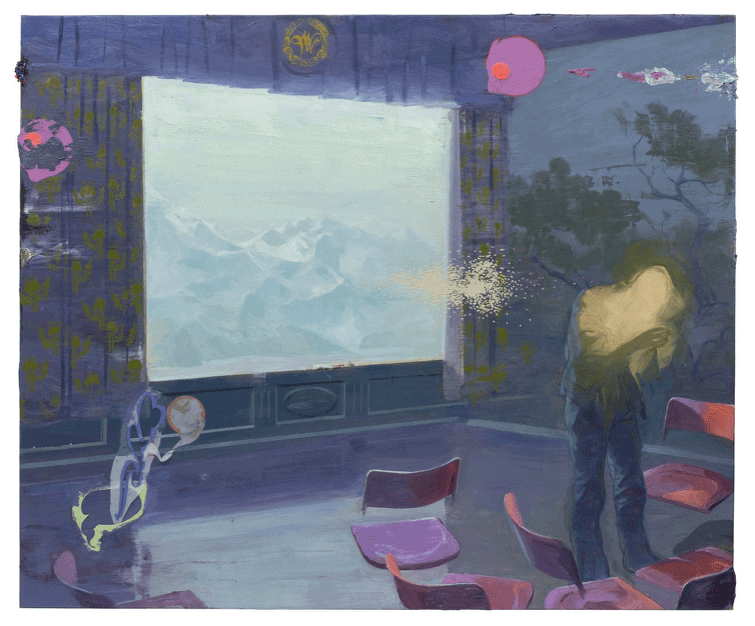

Personally, when I am browsing through your work, what staggers me the most is the immense variety of compositions and figures. Some images seem beyond the absurd, depicting scenes that a feverish dream could not even induce. Could you tell us more about how these compositions and images are built?

RVK

Composition is probably the key. I am obsessed with compositions; they are the backbone of every painting and offer so many possibilities to influence the emotional expression of a painting. It’s possible to counter very extreme imagery with a very orderly composition or vice versa. I am always envious of film directors because they have a timeline, music, and sound available to them. So to me, it’s important to introduce a sense of a before or after into the painting. A strong sense that something must have led up to the depicted moment and that something will happen afterward. Thinking about my paintings that way opens up so many possibilities of expression to me.

JD

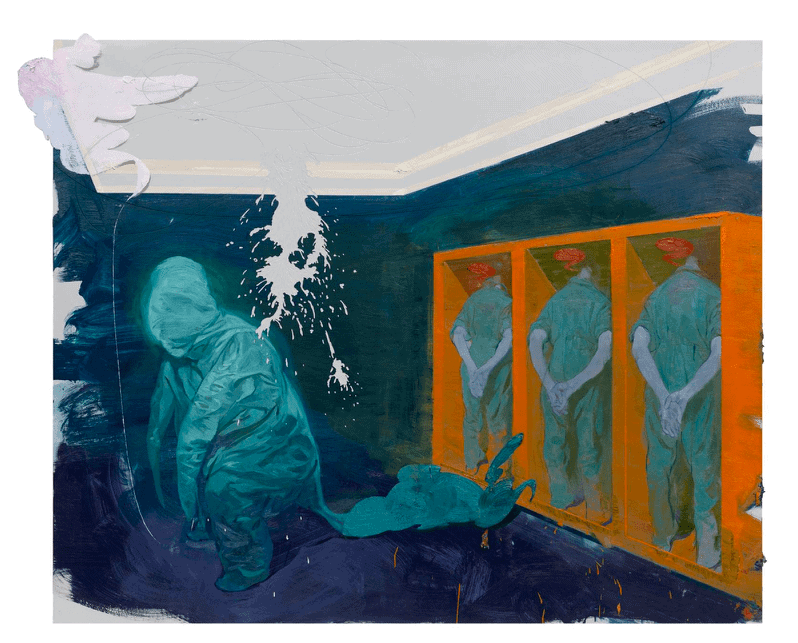

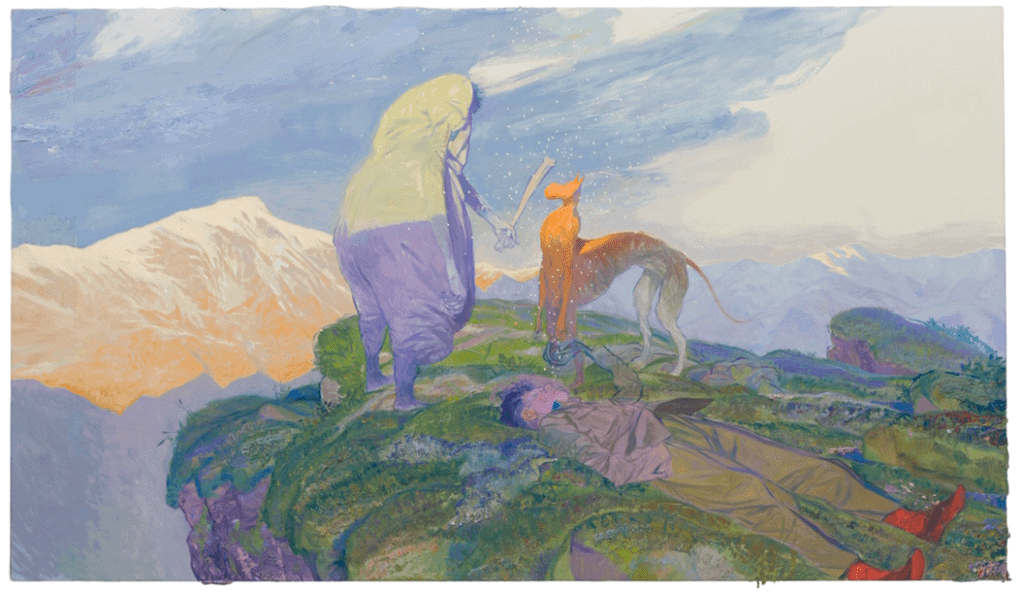

I can not help but smile when seeing this particular painting, Die Gefährten – The Fellows in English – from 2015. Does it look like a small dinosaur is captured in a morph suit? A fascinating intersection of pure science fiction and a hallucination of some sort. Could you talk us through the process, how the image originated, and how one should/could approach this painting?

RVK

There is no right way to approach a painting. It’s allowing yourself to buy into the internal logic of the painted world, to dive into the mood. I try with my paintings to generate a ‘parallel’ reality that somewhat mirrors our own but is strange enough to feel unsettling, like how our own behavior might look to someone looking in from the outside. So by allowing yourself to slip into the painting, I hope you come out of it with a slightly altered perspective on your own life. Ideally.

In this painting, the main character is the ‘monster’ lumbering about. I like your description of a dinosaur captured in a morph suit. I was trying to get this creature that looks sort of cozy and soft and unthreatening, but at the same time, feels unnerving because the shape of the thing is unreadable and obscured. It is, at the same time, familiar and strangely alien.

Then there are the Companions that the painting is named after. The men that are placed in the lockers turn their back to the monster. The inspiration is taken from the Odyssey. There – as in many other hero stories – are Odyssey’s men, who are his faithful companions throughout his adventures. But we never learn their names or anything more about them. They are exchangeable stand-ins, foot soldiers. The ‘sideshow-bob’ of mythology. Disposables that you can pull out of the closet whenever you need someone whom you can turn into a swine.

Even though the painting is kind of dark and moody, it’s one that isn’t meant to be all serious. Usually, there is a lot of humor in my work. So I am glad that it makes you smile.

JD

Another characteristic aspect of your oeuvre, offering visual continuity throughout the variety of scenes and compositions, is your color palette. I note that many blues, purples, pinks, and greens dominate your works’ overall view. They seem to affirm what we’re seeing is not reality.

RVK

When I started out in painting, I was very influenced by the old masters. I was using the ‘old master style,’ and therefore, my paintings had that coloration and light as well. But I always felt it wasn’t quite right. The light didn’t look like light looks nowadays, with neon lamps and all kinds of colorful light sources. I wanted to have a coloration that feels more as if being underwater or in a badly lit nightclub or something. Where skin tones don’t look healthy and pink but are dominated by greens and blue, the effect would be exactly that we do not see something real, but what we are seeing is a reflection of reality, that we are moving through some kind of daydream. Like in dreams, things look familiar, and also not at all like in waking life.

JD

One can ascertain a generation of contemporary figurative painters marked by surrealism and a darker atmosphere rooted in existentialism. In my humble opinion, you have been one of the leading figures for this generation. What’s your view on this tendency in contemporary painting?

RVK

Honestly, I am not very firm about ‘current tendencies’ in contemporary painting. I was always just simply interested in trying to push my work more and more to where I felt it needed to go, to paint the things that go through my head. That has come at the expense of looking too much at what others are doing. That might be arrogant, but for me, it’s a matter of how to spend my time. I am addicted to painting and always think about how to get the next creative hit. So there you are. Of course, there is no greater compliment for an artist than to be able to inspire other artists and no greater honor than to be seen as an artist’s artist. But that’s one of the many things I cannot determine. All I can do is make my work; that’s it.

JD

That makes it even more interesting. It is a very unintentional phenomenon when speaking with the artists associated with this tendency. They all seem to be following their own interests and urges, as do you. Are there certain artists or colleagues with whom you can identify your work? Has there been a reciprocal influence?

RVK

Of course, I am stealing stuff like crazy. But it’s hard to narrow it down to just a few names. And usually, I try not to look at the Instagram feed of people whose work I admire too much out of fear of being influenced too much. I adore the work of Lars Elling (b. 1966), Justin Mortimer (b. 1970), and Nicola Samorì (b. 1977), to name just a few.

But even more, inspiration I draw from song lyrics and from books. I love literature and am addicted to audiobooks (and coffee to complete the trilogy of my addictions). A good book can trigger a million images in my head that I can just run with. That’s why many of my titles are quotes from Song Lyiks or prose. And then, of course, movies: they have been a huge influence on me. In my head, I am directing a film as I paint. There are so many questions that need to be answered in the course of a painting, from composition to lighting, to time of day, to clothes, colors, backgrounds, and how the image will be cropped. All of which influence the final outcome. It is like directing a small movie.

JD

I’ll look forward to the ‘movies’—paintings—you’re set to direct in the coming years. Thank you for your time and even more for your genuine and intriguing view on art, painting, and life. It has been a true pleasure, Ruprecht von Kaufmann.

Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna, AT

Tutorial & Template